Lecture 5

Introduction to Probability

JMG

MATH 204

Tuesday, September 14

Learning Objectives

In this lecture, we will

Introduce the concept of probability as it pertains to statistical applications.

- We will introduce the ideas of random process, outcome, event, probability, and probability distribution. Textbook sections 3.1.2, 3.1.3, 3.1.4, and 3.1.5.

- We discuss mutually exclusive and idependent events. Textbook sections 3.1.3, 3.1.7, 2.1.5.

- We explain the notion of conditional probability. Textbook section 3.2.1.

- We begin our discussion on the imporant notion of random variables.

- We use R to illustrate some of the basic probability concepts.

Why Do We Study Probability?

- Probability forms the foundation of statistics.

Why Do We Study Probability?

Probability forms the foundation of statistics.

Probability provides us with a precise language for discussing uncertainty.

Why Do We Study Probability?

Probability forms the foundation of statistics.

Probability provides us with a precise language for discussing uncertainty.

Suppose we want to know about the average amount of coffee students consume. If we take repeated samples, we will likely get a different mean value for each sample. How much variation is to be expected for the sample mean? This is a question that probability provides us with the tools to answer.

Probability Video

Please review this video at your earliest convenience:

Random Processes

- Consider the game of rolling a single six-sided (fair) die.

Dice as a Random Process

- Tossing a single die provides an example of a random process.

Dice as a Random Process

Tossing a single die provides an example of a random process.

A random process is any process with a well-defined but unpredictable set of possible outcomes.

Dice as a Random Process

Tossing a single die provides an example of a random process.

A random process is any process with a well-defined but unpredictable set of possible outcomes.

For example, we know that tossing a die will result in "rolling" a value of one of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6. However, we can not predict with absolute certainty which value we will roll on any given toss of the die.

Dice as a Random Process

Tossing a single die provides an example of a random process.

A random process is any process with a well-defined but unpredictable set of possible outcomes.

For example, we know that tossing a die will result in "rolling" a value of one of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6. However, we can not predict with absolute certainty which value we will roll on any given toss of the die.

Can you think of another example of a random process? Can you think of an example of a process that is not a random process?

Outcomes of a Random Process

- An outcome for a random process is any one of the possible results from the random process.

Outcomes of a Random Process

An outcome for a random process is any one of the possible results from the random process.

For example, the set of outcomes for the random process of tossing a single six-sided die is the values 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

Outcomes of a Random Process

An outcome for a random process is any one of the possible results from the random process.

For example, the set of outcomes for the random process of tossing a single six-sided die is the values 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

Any collection of outcomes is called an event.

Outcomes of a Random Process

An outcome for a random process is any one of the possible results from the random process.

For example, the set of outcomes for the random process of tossing a single six-sided die is the values 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

Any collection of outcomes is called an event.

For example, the event of rolling a even value is made up of the collection of outcomes 2, 4, 6.

Outcomes of a Random Process

An outcome for a random process is any one of the possible results from the random process.

For example, the set of outcomes for the random process of tossing a single six-sided die is the values 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

Any collection of outcomes is called an event.

For example, the event of rolling a even value is made up of the collection of outcomes 2, 4, 6.

Two events are said to be mutually exclusive if they cannot both happen at the same time. For example, the events of rolling an even number and rolling an odd number after tossing a six-sided die are two mutually exclusive events.

Outcomes of a Random Process

An outcome for a random process is any one of the possible results from the random process.

For example, the set of outcomes for the random process of tossing a single six-sided die is the values 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

Any collection of outcomes is called an event.

For example, the event of rolling a even value is made up of the collection of outcomes 2, 4, 6.

Two events are said to be mutually exclusive if they cannot both happen at the same time. For example, the events of rolling an even number and rolling an odd number after tossing a six-sided die are two mutually exclusive events.

On the other hand the events of rolling an even number and rolling a number less than five are NOT mutually exclusive.

Assigning Probabilities

The probability of an outcome is the proportion of times the outcome would occur if we observed the random process an infinite number of times.

Assigning Probabilities

The probability of an outcome is the proportion of times the outcome would occur if we observed the random process an infinite number of times.

- The probability of any individual outcome for the random process of tossing a six-sided (fair) die is 16.

Assigning Probabilities

The probability of an outcome is the proportion of times the outcome would occur if we observed the random process an infinite number of times.

The probability of any individual outcome for the random process of tossing a six-sided (fair) die is 16.

Note that in general a probability value must be a number between 0 and 1 since it is a proportion.

Some Notation

- In probability theory, we often denote events by capital letters such as A, B, etc., or sometimes even with subscripts such as A1, A2, etc.

Some Notation

In probability theory, we often denote events by capital letters such as A, B, etc., or sometimes even with subscripts such as A1, A2, etc.

We denote the probability of an event, say A by P(A).

Some Notation

In probability theory, we often denote events by capital letters such as A, B, etc., or sometimes even with subscripts such as A1, A2, etc.

We denote the probability of an event, say A by P(A).

For example, if A is the event of rolling an even number after tossing a six-sided (fair) die, then P(A)=12.

The Addition Rule

- If A1 and A2 are mutually exclusive events, then P(A1 or A2)=P(A1)+P(A2).

The Addition Rule

If A1 and A2 are mutually exclusive events, then P(A1 or A2)=P(A1)+P(A2).

For example, let A1 be the event of rolling a number less than 3 and let A2 be the event of rolling a number greater than or equal to 4. (Explain why these events are mutually exclusive.) Then

P(A1 or A2)=P(rolling less than 3, or greater or equal to 4)=P( rolling 1, 2, 4, 5, 6)=P(A1)+P(A2)=P(rolling less than 3)+P(rolling greater or equal to 4)=P(rolling 1, 2)+P(rolling 4, 5, 6)=26+36=56

The Complement of an Event

- The complement of an event is the collections of all outcomes that do not belong to that event. If A is an event, we denote its complement by AC.

The Complement of an Event

The complement of an event is the collections of all outcomes that do not belong to that event. If A is an event, we denote its complement by AC.

Suppose that A is the event of rolling a value less than or equal to 2. Then AC is the event of rolling a value greater or equal to 3.

The Complement of an Event

The complement of an event is the collections of all outcomes that do not belong to that event. If A is an event, we denote its complement by AC.

Suppose that A is the event of rolling a value less than or equal to 2. Then AC is the event of rolling a value greater or equal to 3.

Explain why an event and it's complement are necessarily mutually exclusive.

The Complement of an Event

The complement of an event is the collections of all outcomes that do not belong to that event. If A is an event, we denote its complement by AC.

Suppose that A is the event of rolling a value less than or equal to 2. Then AC is the event of rolling a value greater or equal to 3.

Explain why an event and it's complement are necessarily mutually exclusive.

If P(A) is the probability of an event, then P(AC)=1−P(A). Likewise, P(A)=1−P(AC).

The Complement of an Event

The complement of an event is the collections of all outcomes that do not belong to that event. If A is an event, we denote its complement by AC.

Suppose that A is the event of rolling a value less than or equal to 2. Then AC is the event of rolling a value greater or equal to 3.

Explain why an event and it's complement are necessarily mutually exclusive.

If P(A) is the probability of an event, then P(AC)=1−P(A). Likewise, P(A)=1−P(AC).

The probability of rolling a value of 3 is 16. By the last rule, the probability of rolling any other value besides 3 is 1−16=56.

Probability Distributions

A probability distribution is a table of all mutually excusive outcomes and their associated probabilities.

Probability Distributions

A probability distribution is a table of all mutually excusive outcomes and their associated probabilities.

- For example, consider the random process of tossing two six-sided fair dice and recording the sum of the value of the two dice. Then the possible outcomes are the values 2 through 12. The following table displays the probability for each outcome.

Probability Distributions

A probability distribution is a table of all mutually excusive outcomes and their associated probabilities.

- For example, consider the random process of tossing two six-sided fair dice and recording the sum of the value of the two dice. Then the possible outcomes are the values 2 through 12. The following table displays the probability for each outcome.

| Dice sum | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| Probability | 1/36 | 2/36 | 3/36 | 4/36 | 5/36 | 6/36 | 5/36 | 4/36 | 3/36 | 2/36 | 1/36 |

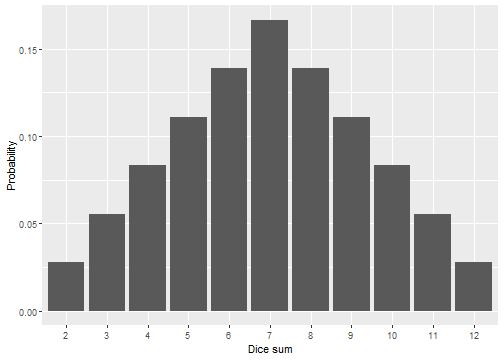

Displaying Probability Distributions

Often, we can display a probability distribution as a barplot; For example,

Independent Events

- Suppose we want to solve the following problem: Toss two coins one at a time, what is the probability that they both land heads up?

Independent Events

Suppose we want to solve the following problem: Toss two coins one at a time, what is the probability that they both land heads up?

It is a fact that knowing the outcome of the first coin toss provides no information about what the outcome of the second coin toss will be.

Independent Events

Suppose we want to solve the following problem: Toss two coins one at a time, what is the probability that they both land heads up?

It is a fact that knowing the outcome of the first coin toss provides no information about what the outcome of the second coin toss will be.

This example illustrates the concept of independence or independent events.

Working with Independent Events

- If two events A1 and A2 are independent, then

P(A1 and A2)=P(A1)P(A2)

Working with Independent Events

- If two events A1 and A2 are independent, then

P(A1 and A2)=P(A1)P(A2)

- We can use this to solve our question from the last slide. The event of landing two heads can be thought of as the event A1 and A2 where A1 is the event that the first toss lands heads and A2 is the event that the second toss lands heads. Then

P(A1 and A2)=P(A1)P(A2)=1212=14

Working with Independent Events

- If two events A1 and A2 are independent, then

P(A1 and A2)=P(A1)P(A2)

- We can use this to solve our question from the last slide. The event of landing two heads can be thought of as the event A1 and A2 where A1 is the event that the first toss lands heads and A2 is the event that the second toss lands heads. Then

P(A1 and A2)=P(A1)P(A2)=1212=14

- Here is an example of two events that are NOT independent. Suppose that A1 is the event of rolling an even number from a die toss and A2 is the event of rolling an odd number from a die toss. Then A1 and A2 are not independent. In fact, mutually exclusive events are only indepent if the probability of one of them is zero.

An Application of Independence

Suppose we randomly select a person. Furthermore, suppose that the probability of randomly selecting a left-handed person is 0.48 and suppose that probability of randomly selecting a person who likes cats is 0.33. We would expect that handedness and prediclection for cats are independent. Thus, the probability of randomly selecting a left-handed person who likes cats is

0.48*0.33## [1] 0.1584Conditional Probability

Suppose we have two jars, one (jar 1) with 3 red marbles and 2 black marbles; and one (jar 2) with 2 red marbles and 3 blue marbles. Next, suppose that we roll a die and if the die rolls 1 or 2 we randomly draw a marble from jar 1 while if the die rolls 3, 4, 5, or 6 we randomly draw a marble from jar 2. Consider the two following questions:

Conditional Probability

Suppose we have two jars, one (jar 1) with 3 red marbles and 2 black marbles; and one (jar 2) with 2 red marbles and 3 blue marbles. Next, suppose that we roll a die and if the die rolls 1 or 2 we randomly draw a marble from jar 1 while if the die rolls 3, 4, 5, or 6 we randomly draw a marble from jar 2. Consider the two following questions:

- What is the probability that we draw a red marble?

Conditional Probability

Suppose we have two jars, one (jar 1) with 3 red marbles and 2 black marbles; and one (jar 2) with 2 red marbles and 3 blue marbles. Next, suppose that we roll a die and if the die rolls 1 or 2 we randomly draw a marble from jar 1 while if the die rolls 3, 4, 5, or 6 we randomly draw a marble from jar 2. Consider the two following questions:

What is the probability that we draw a red marble?

What is the probability that we draw a red marble given that the die rolls a 2?

Conditional Probability

Suppose we have two jars, one (jar 1) with 3 red marbles and 2 black marbles; and one (jar 2) with 2 red marbles and 3 blue marbles. Next, suppose that we roll a die and if the die rolls 1 or 2 we randomly draw a marble from jar 1 while if the die rolls 3, 4, 5, or 6 we randomly draw a marble from jar 2. Consider the two following questions:

What is the probability that we draw a red marble?

What is the probability that we draw a red marble given that the die rolls a 2?

It should seem plausible that these probability values are not going to be the same. In fact, the answer to the first question is 330≈0.43 (we will see how to compute this soon) and it is 35=0.6 for the second (this should be pretty obvious).

Conditional Probability

Suppose we have two jars, one (jar 1) with 3 red marbles and 2 black marbles; and one (jar 2) with 2 red marbles and 3 blue marbles. Next, suppose that we roll a die and if the die rolls 1 or 2 we randomly draw a marble from jar 1 while if the die rolls 3, 4, 5, or 6 we randomly draw a marble from jar 2. Consider the two following questions:

What is the probability that we draw a red marble?

What is the probability that we draw a red marble given that the die rolls a 2?

It should seem plausible that these probability values are not going to be the same. In fact, the answer to the first question is 330≈0.43 (we will see how to compute this soon) and it is 35=0.6 for the second (this should be pretty obvious).

The second question illustrates the concept of conditional probability. Let's examine this concept a little further.

Computing Conditional Probabilities

A mathematical expression for conditional probability may be written down:

The conditional probability of outcome A given condition B is computed as follows:

P(A|B)=P(A and B)P(B)

Computing Conditional Probabilities

A mathematical expression for conditional probability may be written down:

The conditional probability of outcome A given condition B is computed as follows:

P(A|B)=P(A and B)P(B)

- Example: Suppose that we roll two dice, and let F be the event that the first die rolls a 1 and S be the event that the second die rolls a 1. What is the probability that the second die rolls a 1 given that the first die rolls a 1, that is, what is the probability of the event S|F? We can use the previous equation to compute this:

P(S|F)=13616=13661=636=16

Computing Conditional Probabilities

A mathematical expression for conditional probability may be written down:

The conditional probability of outcome A given condition B is computed as follows:

P(A|B)=P(A and B)P(B)

- Example: Suppose that we roll two dice, and let F be the event that the first die rolls a 1 and S be the event that the second die rolls a 1. What is the probability that the second die rolls a 1 given that the first die rolls a 1, that is, what is the probability of the event S|F? We can use the previous equation to compute this:

P(S|F)=13616=13661=636=16

- Question: Is this the result you would have expected?

Multiplication Rule

If A and B are two events, then

P(A and B)=P(A|B)P(B)

Multiplication Rule

If A and B are two events, then

P(A and B)=P(A|B)P(B)

- Reconsidering our game of rolling a die and drawing marbles from a jar, what is the probability of rolling a 2 and drawing a red marble? We can use the multiplication rule. Let A be the event that we draw a red marble and B the event that we roll a 2. Then,

P(A and B)=P(A|B)P(B)=3516=330=110

Another Perspective on Independence

It is a fact that two events A and B are independent if P(A|B)=P(A).

Another Perspective on Independence

It is a fact that two events A and B are independent if P(A|B)=P(A).

- This follows from the definition of conditional probability and the multiplication rule for independent events:

P(A|B)=P(A and B)P(B)=P(A)P(B)P(B) assuming independence=P(A)

The Law of Total Probability

If B1,B2,B3,…,Bn are all exclusive, and if A is any event, then

P(A)=P(A|B1)P(B1)+P(A|B2)P(B2)+⋯+P(A|Bn)P(Bn)

The Law of Total Probability

If B1,B2,B3,…,Bn are all exclusive, and if A is any event, then

P(A)=P(A|B1)P(B1)+P(A|B2)P(B2)+⋯+P(A|Bn)P(Bn)

- We can use the law of total probability to compute the probability that we draw a red marble in our die toss marble draw game. Let A be the event that we draw a red marble, let B1 be the event that we roll a 1, let B2 be the event that we roll a 2, and let B3 be the event that we roll 3, 4, 5, or 6. Notice that B1, B2, and B3 are exclusive. Therefore, by the law of total probability

P(A)=P(A|B1)P(B1)+P(A|B2)P(B2)+P(A|B3)P(B3)=3516+3516+2546=130+130+830=1030≈0.33

Break for More Examples

Let's take a few minutes to work some examples from the textbook for the probability topics we have covered so far.

Introduction to Random Variables

- It's often useful to model a process using what's called a random variable.

Introduction to Random Variables

It's often useful to model a process using what's called a random variable.

Suppose we toss a coin ten times and add up the number of heads that have appeared. Tossing a coin ten times is a random process, the total number of heads after ten tosses is a random variable.

Introduction to Random Variables

It's often useful to model a process using what's called a random variable.

Suppose we toss a coin ten times and add up the number of heads that have appeared. Tossing a coin ten times is a random process, the total number of heads after ten tosses is a random variable.

In general, a random variable assigns a numerical value to events from a random process.

Introduction to Random Variables

It's often useful to model a process using what's called a random variable.

Suppose we toss a coin ten times and add up the number of heads that have appeared. Tossing a coin ten times is a random process, the total number of heads after ten tosses is a random variable.

In general, a random variable assigns a numerical value to events from a random process.

We will see later that random variables have distributions associated with them, and we want to be able to describe the distributions of random variables.

Introduction to Random Variables

It's often useful to model a process using what's called a random variable.

Suppose we toss a coin ten times and add up the number of heads that have appeared. Tossing a coin ten times is a random process, the total number of heads after ten tosses is a random variable.

In general, a random variable assigns a numerical value to events from a random process.

We will see later that random variables have distributions associated with them, and we want to be able to describe the distributions of random variables.

The sample mean is an important example of a random variable and its distribution is called a sampling distribution.

Notation for Random Variables

- We typically denote random variables by capital letters at the end of the alphabet such as X, Y, or Z.

Notation for Random Variables

We typically denote random variables by capital letters at the end of the alphabet such as X, Y, or Z.

For example, let X be the random variable that is the sum of the number of heads that we obtain after tossing a coin ten times. The possible values that X can take on are X=0, X=1, X=2, …, X=10.

Notation for Random Variables

We typically denote random variables by capital letters at the end of the alphabet such as X, Y, or Z.

For example, let X be the random variable that is the sum of the number of heads that we obtain after tossing a coin ten times. The possible values that X can take on are X=0, X=1, X=2, …, X=10.

Typical questions that we ask are ones such as, what is the probability that X=2, or what is the probability that X is less than 5. What do these questions mean in the context of our coin tossing example?

Notation for Random Variables

We typically denote random variables by capital letters at the end of the alphabet such as X, Y, or Z.

For example, let X be the random variable that is the sum of the number of heads that we obtain after tossing a coin ten times. The possible values that X can take on are X=0, X=1, X=2, …, X=10.

Typical questions that we ask are ones such as, what is the probability that X=2, or what is the probability that X is less than 5. What do these questions mean in the context of our coin tossing example?

- The distribution of X allows us to answer such questions.

A Look at Some Data

- Let's look at six rounds if tossing a coin ten times. At each toss, we record 1 if we land heads and 0 if we land tails. Then we can add up the 1's to get the total number of heads after ten tosses. Our data might look as follows:

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | X6 | X7 | X8 | X9 | X10 | total_heads | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| round_1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| round_2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| round_3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| round_4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| round_5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| round_6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

A Look at Some Data

- Let's look at six rounds if tossing a coin ten times. At each toss, we record 1 if we land heads and 0 if we land tails. Then we can add up the 1's to get the total number of heads after ten tosses. Our data might look as follows:

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | X6 | X7 | X8 | X9 | X10 | total_heads | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| round_1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| round_2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| round_3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| round_4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| round_5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| round_6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

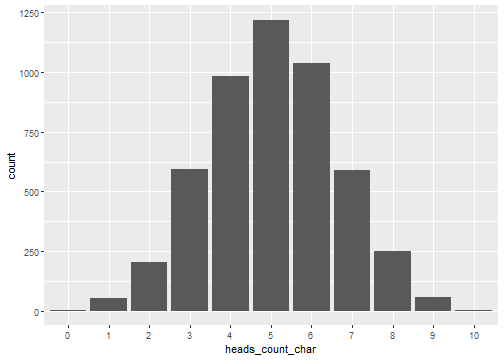

- Let's repeat this process many more times and create a barplot that shows the number of times each of the values 0, 1, ..., 10 occurs.

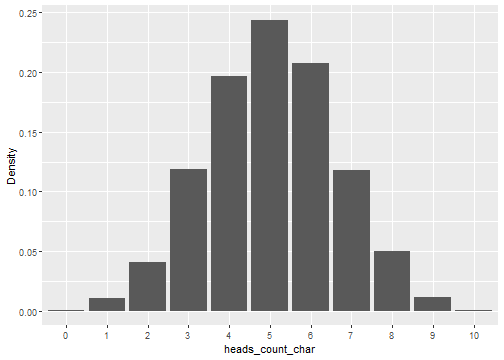

The Distribution of the Number of Heads

The Distribution of the Number of Heads

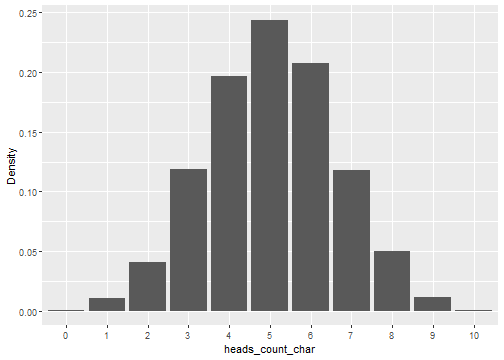

- If we divide all of the counts by the total, we get the density. This provides an estimate for the probability value of each outcome.

Probabilities for Number of Heads

This plot show the density instead of count for the previous barplot.

Probabilities for Number of Heads

This plot show the density instead of count for the previous barplot.

- From this plot, we can easily estimate probability values. For example, what is the pobability of getting 4 heads out of ten tosses? It's about 0.2. What is the probability of getting less than three heads? It's about 0.04 + 0.01 + 0.0025 = 0.0525.

The Mean and Variance for Number of Heads

We can compute the mean and variance for the number of heads, in which case we get:

## [1] "The mean is 5.038600"## [1] "The variance is 2.565623"The Mean and Variance for Number of Heads

We can compute the mean and variance for the number of heads, in which case we get:

## [1] "The mean is 5.038600"## [1] "The variance is 2.565623"- This tells us that the "average" number of heads out of ten tosses is about 5. How does this correspond with your real life experience or expectations?

The Mean and Variance for Number of Heads

We can compute the mean and variance for the number of heads, in which case we get:

## [1] "The mean is 5.038600"## [1] "The variance is 2.565623"This tells us that the "average" number of heads out of ten tosses is about 5. How does this correspond with your real life experience or expectations?

These values provide estimates for the expected value and variance of our random variable. These concepts will be defined and discussed in detail in the next lecture.

Next Time

In the next class,

Next Time

In the next class,

- We will have our first data lab assignment.

Next Time

In the next class,

We will have our first data lab assignment.

With whatever time is left, we will continue our introduction to random variables.

Next Time

In the next class,

We will have our first data lab assignment.

With whatever time is left, we will continue our introduction to random variables.

Before the next class, make sure to accept an invitation to the MATH204LabAssignment01 RStudio Cloud project.